Minerality. It is a commonly used descriptor for flavours, usually in white wine, and usually those from the northern extremes of wine production in Europe, leading some to say that it might be a synonym for acidity or austerity. Others say the perception of chalky, slatey, flinty elements in wine is conveyed by sulfur compounds, especially mercaptans. The vine selectively absorbs single metallic cations and small anionic compounds, which taste the same – if they taste of anything – regardless of their place of origin, yet some commentators talk as if vines are passive conduits of complex mineral compounds between the soil and the grape giving rise to iron flavours in iron-rich soils and chalky or oyster shell flavours in wines produced on limestone.

What is this thing called minerality? It didn’t appear in wine writing until the 1980s and is still shunned by some. Is it a valid reproducible descriptor or does it mean all things to all men?

A couple of weeks ago I presented a line-up of German Rieslings to the Magnum Society in Wellington and took the opportunity to gather some data on my colleagues’ perception and understanding of the term minerality. WARNING. This is going to get a little geeky, so if you think that wine should be about romance not statistical analysis, look away.

Method: Six 2005 German Rieslings were presented blind. They were as follows: Loosen Erdener Treppchen Riesling Kabinett; Fritz Haag Brauneberger-Juffer Riesling Kabinett; Schaefer Graacher Domprobst Riesling Spätlese; Dönnhoff Norheimer Dellchen Riesling Spätlese; Dönnhoff Oberhäuser Brücke Riesling Auslese; and Fritz Haag Brauneberger-Juffer-Sonnenuhr Riesling Auslese.

The 19 participants were asked to rank the six wines in order of minerality, the “1st” being the “most mineral”; whether that be the “strongest mineral flavour” or “best exemplifying the concept of minerality”, the “6th” being the least. The participants recorded their rankings independently on paper slips, which were collected before any group discussion on the wines took place.

Results: Data on each wine was analysed separately using the Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test (you were warned) to determine whether the rankings were random, in which case minerality would have little value as a descriptor. The p value was 0.00042, meaning that this was extremely unlikely to be due to chance.

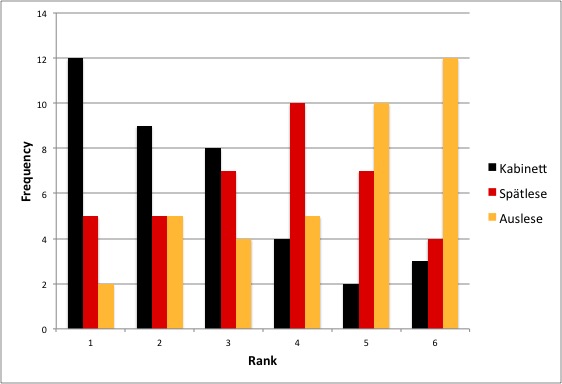

Frequency (y axis) of each of the 6 rankings, 1st through 6th, (x axis) for the three different Prädikat levels.

The main finding of the exercise is best demonstrated by comparing the frequencies of each ranking for each of the three Prädikat levels (see figure). This shows that participants more commonly gave high rankings for minerality to wines with low levels of residual sugar, the Auslese wines most commonly getting the lowest rankings.

Conclusion: There was a high level of agreement between participants, indicating that this descriptor is ‘similar things to most men’ (and women of course, although there were too few present for sub-analysis by gender). The tendency to rank wines with lower residual sugar as more mineral that the higher Prädikat wines supports the view that minerality is a surrogate for austerity and acidity, or that minerality is masked by sugar.

References: