This is part one and two of the trip report. I’ll update the title and this section as the report itself is updated.

Friuli remains an incredible wine region to visit. Not only is it incredibly beautiful, but the hospitality is deep and sincere, the food is good, and there’s plenty to see and do that’s not wine, as well. More importantly, the wines are great and the conversation around those wines—about the nature of geography and culture, history and tradition—is some of the most fascinating out there.

So, upfront, there’s good news and bad news. I managed to leave my notebook in our rental car and so will be recalling all the fun details and tasting notes from memory (with a few assists from the internet) and I know I will miss some things. BUT the flip side is that this is forcing me to put it down on (virtual) paper, as opposed to our last trip ~three years ago, when I kept procrastinating the write-up before eventually deciding that no one wanted a 14-month old trip report and gave up.

We flew into Venice on Saturday the 18th and collected our rental car for the drive to Udine. We stayed in Cormons on our last trip, but had a three-month old in tow this time and figured if one of us (Sonya) was going to walk around dealing with a fussy child instead of going to a winery, there was more to do in Udine. La bambina ended up being pretty content, so this ultimately didn’t matter as much, but Udine is a fun city to walk around and the dining has a lot more variety than Cormons.

Day One: Ronchi di Cialla and Mitja Sirk

Ronchi di Cialla

We opened this trip on Monday the same way we started the last giro d’vino: with a visit to the incredibly gracious (and talented) Rapuzzi clan at Ronchi di Cialla. Ivan and his mother, Dina, were there to greet us and welcome us into their home/winery, which is one of the most comforting, classic places to drink wine out there.

The wood-fired stove was smoldering in the next room, warming us as it prepared to make lunch for the family after we left. Ivan speaks excellent English, and is an exceptionally curious person. No one else asked nearly as many questions about viticulture in Oregon, and he (and his brother Pierpaolo, who joined us later) are both real evangelists for the grapes of Friuli and excited to see them planted abroad.

I get the sense that the wines of Ronchi di Cialla remain a bit overlooked in the marketplace (ok, that’s true of most of Friuli) but they remain one of the touchstone producers in the region for me. Part of that is due to their historic legacy—we largely owe the existence and relative popularity of Schioppettino (Friuli’s great native red grape, IMO) to Dina and her late husband Paolo—but also the wines have always been ageworthy and delicious without sacrificing the character of the area by an iota.

The caveat for this visit is that I’m a very unusual person w/r/t what I’m after in tastings on this trip. They asked what I wanted to try (and I know they’d be happy to open the full lineup—they did last time) but I was mostly there to ask questions about farming and vinification of native grape varieties. I also tend to buy and open these at home, so I’m familiar with enough of the wines that this wasn’t just a chance to taste new things.

We started with the 2023 (? I have it in my head that we may have tried the newly bottled ‘24, but the answer is probably in the dumpster by the Hertz at Marco Polo airport) Friulano (locally, winemakers still call the grape Tocai), which I’d never had before. Fermented with native yeast, like all their wines, in stainless steel and aged briefly, it’s definitely their “no worries” white. Talking to them, Tocai is very much not their focus as white-grapes go (that’d be Ribolla Gialla), but this bottling is quite delicious and a bit smaller-scaled than many renditions of the grape.

One of the things that’s often challenging with Tocai is its tendency to put on sugar in the vineyard while it ripens, but the ‘23 (and ‘24) vintages seem to favor a little lower alcohol and more elegance in the glass. Both were tough vintages, at least when it comes to the peace of mind of the winemakers (more on ‘23 in Tocai when we come to the next producer, especially)—but I often found the wines to be excellent.

Next up was the new vintage of the RiNera (aka the Ribolla Nera, aka their entry-level Schioppettino). I for the life of me don’t remember the vintage in question—I’m 75% confident that it was the ‘23, but have emailed Ivan to see if he can give me updates—but as always this is just a delightful wine.

Schioppettino is their signature grape, and in my opinion the great red grape in Friuli. Ronchi di Cialla produces two bottlings of it, and this is their “entry” bottling which is aged entirely in stainless steel. Both wines see 10-14 days on the skins, but this version is always so energetic and fresh. For those who are unfamiliar, Schioppettino has a more-than-passing resemblance to Pinot Noir in its use at the table and thin skins, but with a distinctive black pepper note that’s always captivating.

It’s a notable grape for how much of a PITA it is to grow, which is due in no small part to it’s ancient lineage. It’s practically a pre-vinifera grape—Ivan mentioned there are basically no real relatives, and it dates back to the 13th century—and so its growth habits are really unusual for modern viticulture. Add in a sensitivity to mildew over the summer and a looooong hang time (120-140 days, though it seems to tolerate rain in the fall) and you have a variety that’s a real labor of love.

Their 2018 Schioppettino is a clear step up—Ivan and Pierpaolo think that it’s one of the great vintages at the estate—and it’s the current release, I believe. Aged in mostly used barriques (~10% are new, mostly as a way to ensure a consistent supply of clean barrels) it’s a beautifully transparent ruby in the glass and on the palate. This is a wine of complexity and intensity without much weight, and has a long life ahead of it if the library vintages they regularly offer are any indication.

We talked for a while (2+ hours) and I’ll spare everyone all the boring details, though the conversation ranged from why they stopped producing a Pignolo (it’s just more rustic than they’re after with their wines, though some remains planted for the Ciallarosso) to a lot of questions about site selections and how they differentiate the different bottlings (typically, the same plots go into the higher- or lower-end bottlings, but in exceptionally warm or cool vintages that might not be true.

Since we didn’t taste them here, and they also don’t get enough attention, I’ll also mention that I really love the Ciallabianca, which is their blend of Ribolla, Verduzzo, and Picolit. It’s always a beautiful wine and it ages exceptionally well. Their Verduzzo (dessert) is always a favorite and the Ciallarosso and Refosco are both excellent as well.

Mitja Sirk

If you’ve been to—or heard of—La Subida, Mitja’s name is familiar. His family’s inn and restaurant is one of the great destinations in Friuli, and their wine list is one of the world’s greats for its combination of depth and focus, in my opinion.

Mitja (who gave a great interview to Levi Dalton back in the day on I’ll Drink to That) grew up in the restaurant and is its day-to-day ambassador on the floor. But he’s not just incredibly knowledgeable about the wines of Friuli: He’s exceptionally passionate about the wines of the world and boasts an impressive resume of harvest experiences and apprenticeships.

The focus here is on Tocai and this is, without a doubt, the place where I’m most annoyed that my notes are gone. Mitja makes both some single-vineyard bottlings and also a “Bianco di Mitja” which is still sourced from some incredible sites. Sites which, alas, I no longer can talk about quite as intelligently.

The first thing that’s of interest to me is that he’s working with vineyards on both sides of the Slovenian border for his entry-level bottling, which is made to be approachable and useful to restaurants in the area and abroad. Administratively (and from a certain marketing perspective), this is a real pain: the Bianco is now bottled just as a “Vino Bianco Europeo.”

But looking at a map, it’s easy to see why he’s gone down this path: the Brda in Slovenia and Collio in Friuli are geologically the same region, and share a climate as well*. There are plenty of old vines there and capable farmers, but the demand for the grapes is lower.

He also produces two single-vineyard bottlings: The first is called Ca’ Savorgnan, which comes from a vineyard in Cormons that’s blessed with very old vines (~85 years). When he originally took over farming this (before his first vintage) most of the vines had died out. He’s replanted a lot within the plot, but this comes from the survivors. The other, Meden, is slightly younger (~65 years) from a site farther afield that he shares with Marta Venica. Both are excellent.

We had a really engaging conversation about vintages in Friuli. The most recent, 2024, was a nightmare for anyone growing grapes in a lot of ways. Yields were slashed because of frost and hail—which occurred early in the year and destroyed shoots before they even had to flower—and then further from disease pressure though the summer. But what did make it into the tank is really delicious to my palate. It’s another small(er) scaled vintage, which for often-big-boned Tocai isn’t the worst thing, but the wines we tasted seemed to have plenty of persistence on the palate and complexity even at this stage.

2023 was an odd year that featured worries about botrytis near harvest. Normally the goal is to harvest Tocai as the noble rot strikes a berry or two here or there—any longer and the fungus quickly moves through the bunches, but it’s a signal that the grapes are perfectly ripe—and Mitja was saying that he’s generally pretty confident in what he’s going to see a week or so out.

In ‘23, that hint of botrytis appeared earlier than expected vis-a-vis sugar ripeness and acids seem to be falling, and so he moved to harvest quickly, deciding that purity was worth any gains in ripeness. The wines are lighter in body, often below 13% alcohol (which he’d have thought an impossibility for high quality Tocai in previous years) and yet seem to be fleshing out nicely with balance and poise. I was a fan.

2022 is the opposite: A warm year that produced big, broad-shouldered bottles of real intensity and power. Mitja was candid that when they were in fermenter and first bottled, he wondered if they were too much, but time has rounded away some of the baby fat and revealed really interesting wines. We had both ‘22 Ca’ Savorgnan and ‘22 Meden out of bottle and while they both will never be confused with cool-vintage wines, they seem to have a long life ahead of them.

We also had the chance to taste the ‘19 Ca’ Savorgnan, which was an absolute showstopper on the night and proof that I need more of his wines in my cellar, and with more age. When you talk to Mijta and taste the wines, it’s clear that he’s already in the top class of producers in the region and has the intellect and curiosity to continue to refine the wines further.

__

*A few other winemakers, when talking about this, pointed out that there are real differences w/r/t culture and cuisine—it’s telling that the first modern orange-wine producers were ethnically Slovene—and so lumping in Friuli and Slovenia isn’t as straightforward as it seems.

Day Two: Burja Estate and Kmetija Hedele (Vipava Valley)

When we were planning the trip, Mitja Sirk suggested a bunch of producers that weren’t entirely on my radar, but by far the most interesting (to me) was an excursion to the Vipava Valley in Slovenia. Roughly a half-hour from the Collio/Cormons (or a little over an hour from Udine, where we were staying), it’s very much within the same climatic and geologic region.

In Oregon terms, we’re talking the distance from Portland to Newberg—yet I think most American drinkers think of Slovenian wines as far more “distant” from Italy as those two points within the Willamette Valley.

It was a foggy, grey day with a decent bit of rain, but it’s clear how beautiful the Vipava Valley is even in winter. I can only imagine how gorgeous it is during spring or summer, when the forests undoubtedly spring to life and the hillsides are paved with green. On a tourist-related note: dear god, everyone in Slovenia was so nice and most spoke incredible English. I can’t wait to go back.

Burja Estate

I first tried the wines from Burja years ago, in 2011 or thereabouts, when Indie Wineries imported the wines into Nashville via the distributor 100% Italiano. At the time, they were eye-opening: interesting, well-made bottles that spoke strongly of a place I’d never considered before—at exceptional prices. The Zelen, in particular, was a wine I drank a lot of and it’s always been fun to see it on a shelf or a wine list.

These days, the winemaking at Burja is a bit different than the early days—skin contact is the focus here now—but the soulfulness of the wines still comes through, and the hospitality that Primož and Mateja Lavrenčič showed us was exceptional.

I think we’d been in the door for two minutes, and I turned around and Mateja was already holding our baby, Esther—and that sense of familial joy permeated their interactions with us. Both are incredibly thoughtful about the wines they make and how they represent the region, but also there’s a sense that wine is made to bring people together.

The winery itself is gorgeous (more on that later) with a tasting area that looks like it was out of either my dream house or an architectural magazine. Primož remarked later that they’d never be able to build the winery today because prices have gone up so much, so he’s very glad they went for it in 2015 (during the early days of the winery). They also served us a selection of cheeses and cured meats from Vipava, which were excellent—though Mateja commented that only a few producers in the regionmwere working to make world class cheese.

We started with 2023 Grašica (aka Welschriesling), which is a workhorse grape in the region. Historically it delivered solid yields of grapes that ripen well in the climate and so it was popular with small farmers (in 2024, yields were down in all the grapes except Welschriesling). Primož pointed out that despite the name, it’s historically a variety associated with the Austro-Hungarian Empire, so it’s been popular in Slovenia for a long time. The bar is low for the best Welschriesling I’ve ever had, but this cleared it with ease and had lovely flavors of white-peach fruit, spice, and nice length on the palate.

It showed off the current Burja winemaking philosophy to excellent effect: The wine was macerated on the skins (for a few weeks, in the case of this wine, longer for some of the others) because Primož has grown to feel that skin contact is integral to his vision of white wines. He feels like it properly extracts the character of the grape and place in a way that’s impossible through simply pressing the juice out, but he’s not after oxidation, so maceration takes place in stainless steel. In general, the wines all feel Natural but composed—if you hate Natural Wine, you’ll probably find some nits to pick, but given the genre, they’re nicely put together.

We moved on to Zelen, a grape historically grown solely in this part of the Vipava Valley. The name means “green” because it stays green and slightly dusky looking even as it ripens. (I wish I had the exact quote, which is written down in the lost notebook, but Primož point was basically “hey, they’re farmers, it was a pre-industrial world. How else are you gonna name a grape?”) I’ve always found this wine fascinating for it’s bold aromatic stance and beautiful fruit and while I might have liked the direct-pressed versions made in the early days a bit better, it’s still a delicious bottle to drink.

The next two wines, Burja’s 2023 Bela and 2020 Stranice, are both made in the same vein: co-fermented blends of Rebula (Ribolla Gialla), Malvazija (Malvasia Istriana, which is always more saline to me than any other Malvasia variety from the rest of Italy), and Welschriesling. They point out that this is basically a Collio-style blend, where the Rebula and Malvazija occupy the traditional roles of acidity/palate length and aromatics, respectively—but instead of Tocai Friulano providing the body and richness, Grašica (Welschriesling) is in its place to fill out the mid-palate.

As in the Collio, it works really nicely here. Bela is a selection from various points around their estate, and Stranice is a single-vineyard bottling from 65+ year old vines (that Primož worries will have to be replanted soon) and sees a bit longer on the skins. Both feel a bit more “orange” than the first two whites and see longer skin-contact. Both had excellent complexity and depth—the Stanice was absolutely singing, really rewarding the extra couple years of bottle age.

(Speaking of age, we drank a 2010 Burja Bela at La Subida in ‘22 on our last trip to Friuli, and it was outstanding. That wine was made in the old style for the estate—direct pressed, no skin contact—but was absolutely singing. I don’t know if the new wines will age like that, but if I came across Burja bottles from that time period I’d snap them up.)

At this point, we headed down into the cellar, which was a highlight in and of itself.

Vipava sits on ponca soils, which is generally defined as a mixture of sandstone and calcareous marls—though I don’t believe there’s a strict geologic definition—and walking down into the cellar is a lesson in how the soil behaves. The cellar was dug out in a way that left plenty of the soil exposed, and the uplifted bands of the two parent materials were one of the coolest cellar-walls I’ve seen. (My pictures don’t do it justice.)

The bands have been pitched upwards thanks to tectonic activity in the millenia since the ancient sea-bed compacted—unlike Burgundy, Primož notes, where the bands of parent rock still basically lie horizontally—which creates plenty of variation in the soils on a meter-by-meter basis. The limestone bands are significantly more friable and also hold water, while the sandstone is harder and basically imporous.

Because they were excavating so much sandstone—and because it’s a coveted building material—they decided to build much of the cellar’s structure out of blocks of it, to stunning effect. It’s also laid out in a way that permits gravity-flow winemaking and easy access to the wines at all stages. Despite all this, it never felt like the architecture was particularly trying to show off, and it was a mile off some of the vanity projects I’ve toured in Napa. There’s still real soul here. I was more than a little jealous.

We tasted a number of the 2024 whites and 2023 reds out of tanks and barrels—still young, showing promise, but this section is getting long enough as it is—and then moved back up to the tasting room to taste a few reds out of the bottle.

Primož is enthusiastic about Pinot Noir, which is the only non-autochthonous grape planted in his vineyards—and his 2022 would fit in pretty well in a lineup of good Oregon wines in both quality and style. ‘22 was a warm vintage, and this shows the year’s ripeness in a mixture of red and dark fruit. It’s made from a mixture of 114, 115, and 777 clones, if I recall correctly, and is mostly de-stemmed. Overall, there’s a bit of looseness to the edges that hint at its natural origins, but I appreciated its balance and profile.

There’s also a red blend, called Reddo, which is made from a mixture of Pokalca (Schioppettino), Modra frankinja (Blaufränkisch), and Refošk (Refosco). The peppery notes of Schioppetino come through on the nose—along with a bit more VA than the rest of the wines, though YMMV in how much it bothers you—and the palate is nicely energetic while being middle-weight and full of savory red plum, tart blackberry, and riper red currant notes, dusted with herbs.

At this point, we realized that we were going to have to hustle to make our next appointment, and headed out for a sandwich and then to a visit with Andrea Pittana at Kmetija Hedele.

Kmetija Hedele

So I’ll put my cards on the table early with this one: This was the most exciting group of wines we tasted on the trip—both because of the quality (absolutely great) and because I’d never registered a whisper about them before Mitja mentioned I should visit (which, to be fair, might entirely be me—but also I’m not normally the last to know).

The former wine-retailer in me is screaming “don’t hype wines until you have an allocation,” but Hedele now have an American importer (Benvenusa, Bobby Stuckey’s new company) and there’s no way the wines are going to stay a secret over here. I think they’re already well-respected by those in the know in Europe.

The counterpoint to this (and I should get this out of the way, so I can just go back to positives) is that I don’t know if I’d recommend that anyone visit Andrea—at least unless they speak Italian and are comfortable with what is, at the moment, a very rustic tasting experience. I know un po’ Italiano and plenty of wine words (and understand more than I speak) and am used to working in cellars, so I really enjoyed it, but it was not a voluminous conversation.

Andrea, to his credit, tried to mostly speak English—out of a sense of politeness—and took a bit to open up, but I think if you went as with/as a true Italian-speaker you might have an even better time. His winery is currently housed (quite literally) in four or five separate/neighboring houses in Gaberle, a small rural Slovenian village in the hills above Ajdovščina.

They’re in the process of renovating them and turning one into a tasting room, which is where we tasted out of bottle after going through a few barrels in the cellar. At the moment, I don’t believe the tasting room has either lights or heat (it was the same temperature as the cellar) but that might change soon.

So, on to the unreserved enthusiasm.

Andrea is a hugely respected figure within the wine industry in Friuli. His day job is very much not Hedele, but rather as a consultant in both enology and viticulture to some of the most important names in the region. He’s a pretty modest guy based on my interaction with him and didn’t name any names, but Mitja Sirk mentioned he worked on the vineyard side with Gravner and then Mario Zanusso at i Clivi declared that Andrea has been instrumental in multiple facets of the operation as a consultant. Anytime his name came up on the trip, the chorus was the same: “he’s one of the most knowledgeable people out there.”

Hedele is named for the old cadaster parcel-name of the first vineyard he bought in Vipava. The plan wasn’t particularly to go down this path, but he’d been helping a client identify and purchase the site when the client changed their mind—and basically he felt the site was too interesting to pass up himself.

When he bought it, it was unplanted, and now has Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, and Malvasia Istriana—the only three grapes he works with under the label. He’s since added another vineyard, Obelunec (again the cadaster parcel-name), which has rockier soils and I believe only has Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc planted.

We started in his cellar—again made out of sandstone, though much, much older than the one at Burja—and tasted wines from barrel. All three grapes see fermentation in wood with native yeasts that start as a pied de cuve (aka a starter) that he makes in the cellar a week or so before harvest. Chardonnay and Malvasia are pressed, settle gently, and then go straight into barrel, while Sauvignon Blanc begins fermentation in stainless steel. Andrea believes it’s important for Sauvignon to have a vigorous ferment and the larger mass of a stainless steel vessel builds temperature and cell counts to ensure that things move quickly once it gets transferred to wood.

The wines will all spend a year in wood (a little bit is new, but not much) before being racked into stainless tanks on their lees for an additional year prior to bottling. It’s a real time commitment and he seems to hold bottles back before releasing them, as well—we tried the 2020s out of bottle.

Despite their youth and the tougher vintage, the set of wines was really lovely already. Malvasia was first and the barrel fermentation adds a nice layer of complexity and texture to a wine that balances floral aromas with a lively fruit and salt dialectic on the palate. (If you’re reading this and haven’t had any Malvasia Istriana, it’s significantly more savory and saline than most other Malvasia cultivars across the boot.)

Next up is Chardonnay, and the Hedele vineyard shows more richness and sweeter fruit than the wine from Obelunec. Both are in very early stages and show a ton of promise, though they’re both pretty clearly far from their final form (from my own experiences, I’ll say that Chardonnay is often one of the grapes that benefits most from being in the cellar longer than a year).

Finally, Sauvignon Blanc, which we also taste from both Hedele and Obelunec. Both show a decided orchard-fruit aspect of the grape, with a peachy quality and hints of ripe passionfruit. There’s a lot of class in both, and just a bit more focus out of the Obelunec—though if someone preferred the Hedele bottling for its power, I’d totally get it.

Talking with Andrea, it’s clear he has a vision for the wines—he picked these varieties because he thought they had the most potential for greatness in his sites, and I get the sense he’s got a mental picture of how he wants them to be expressed. Tasting out of bottle, it seems to be working.

We taste four wines, all 2020: Chardonnay and Sauvignon from both Obelunec and Hedele. They’re really beautiful—textured but not too rich, with great varietal typicity and lots of complexity. They also feel a bit cooler and more incisive than the wines from those grapes that we taste in Friuli, which reflects the climate and soils—Vipava is ponca but in a different geologic basin* than the Collio/Colli Orientali—of this part of Slovenia.

__

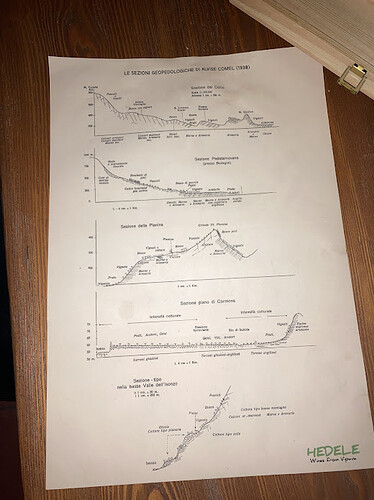

*To that end, Andrea found an old cross-sectional diagram of the soils in various parts of Friuli in a pre-war viticulture book (he’s a bit of an enthusiast when it comes to old viticulture/enology books) and had the image printed on posters. It’s really cool: