cant state with certainty and where i read this but i have a decent enough recollection that there is more vine on limestone surface in spain than in France. can you chime in on this?

Rasoul - several reasons for that. First of all, there is more surface area planted to vines in Spain than in France. Spain has more land under vine than any other country, and it’s about 20% more land under vine than France, which is third, although in terms of wine production, they switch places - France produces more wine than Spain. The reason is that while there’s a lot of land under vine in Spain, much of it is sparsely planted.

Second reason is that the largest wine area in Spain, in La Mancha, is largely limestone.

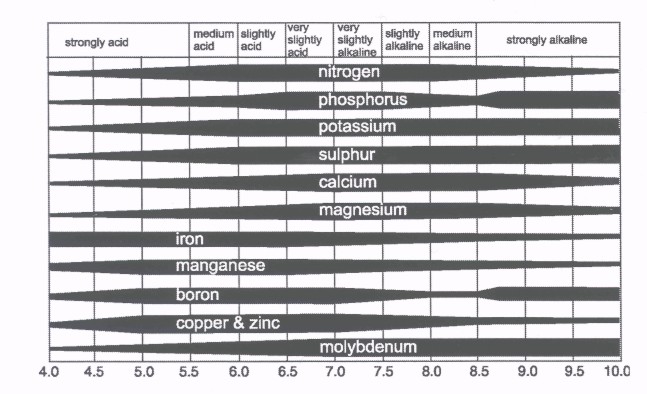

My instincts suggest higher pH [calcareous] soils translate to higher pH wines, which tend toward heightened anthocyanin expression/ likability.

I may be entirely wrong about this, but I think it’s actually the opposite.

great points. i would go ahead and say that it is my strong opinion that chardonnay, then pinot noir then tempranillo are the 3 (in that order) varieties that i believe should be planted on limestone (chalk…) esp chardonnay.

As far as Tempranillo growing on limestone - the Sierra Cantabria mountains in Rioja provide a lot of different soil types. There are alluvial soils near the river, granite and limestone in the hills, and and then you have sandstone and eroded run-off coming down the valleys. The colors range from red to brown to white. Same in Ribera del Duero, where the soils are alluvial with sand and clay near the river and then in the west are gypsum, limestone and marl, where in the east there’s more clay. In Peñafiel there’s sandier soil and in Burgos the soils are sandy with alluvial deposits and again, marl.

I think the reason for “why limestone” is that much of Europe was formed by uplifting an ancient seabed and consequently, much of the soil in France and Spain is limestone. But as many others have pointed out, there’s granite and volcanic soil as well. In Tokaj, which is the first place to have classified vineyards as far as I know, you can see great differences from one vineyard to the next - there’s loess, run-off from the mountains, granite, volcanic soil, and uplift from an ancient shallow sea, all providing different colors and styles of soil.

BTW guys - great thread but the one thing nobody has mentioned yet is that we’re usually not growing Merlot or Chardonnay or Pinot Noir on their own roots. They’re on rootstock that may have a completely different uptake and soil preference than the scion.

BTW - Mel and Peter - great posts. While it is interesting to hear about soil types, what makes or breaks a vintage is always the weather. And of course, that and harvest decisions probably have more to to with acidity in wine than anything else.